“We don’t think the intelligence issue matters when it comes to literacy.

All children can learn to read and write, can become people who matter to the people around them

and can use reading and writing in ways that improve their lives.

–Karen Erickson and David Koppenhaver

Making instructional decisions for students with significant disabilities and complex communication needs

Students with significant cognitive disabilities are individuals with unique learning needs and interests, who with the right supports at the right time, can participate in learning, benefit from literacy instruction, and contribute to the school community.

Karen Erickson reminds us that students with significant disabilities differ markedly from one another. Some are able to read independently with fluency and comprehension, and write for a variety of purposes while others struggle to learn basic academic concepts or process the world around them. Still others have not developed intentional communication and depend completely on caregivers and educational teams to meet all of their needs. (To learn more about students with significant cognitive disabilities, visit Learning for All.)

Our judgments about students’ intellectual capacities affect every decision we make about their educational programming, their communication systems and supports, the social activities we support their participation in, and the futures we imagine for them.

The criterion of least dangerous assumption holds that in the absence of conclusive data, educational decisions ought to be based on assumptions which if incorrect, will have the least dangerous effect on the student. The least dangerous assumption for students with significant disabilities is to presume competence and assume that a student has intellectual ability. Presuming competence means providing meaningful opportunities for learning, including daily reading and writing instruction, and assuming that the student wants to learn and assert themselves in the world.

Presumed competence is a framework and an approach based on the assumption that each child wants to be fully included, wants acceptance and appreciation, wants to learn, wants to be heard, and wants to contribute. By presuming competence, educators place the burden on themselves to come up with ever more creative, innovative ways for individuals to learn. The question is no longer who can be included or who can learn, but how can we achieve inclusive education. We begin by presuming competence. (adapted from Douglas Biklen: “Begin by presuming competence”).

In the video, The Cost of Underestimating the Potential of Individual Students, Dr. Caroline Musslewhite discusses why it is important to not underestimate the potential of individual students, particularly students with significant disabilities.

Video: 1 minute 41 seconds

Learning Guide: The Cost of Underestimating the Potential of Individual Students

Meaningful, purposeful communication

“Meaningful, purposeful communication is at the heart of learning to read and write. Students who learn that they can use reading and writing to investigate areas of interest, share their ideas, thoughts, and feelings, or interact with new people understand that the primary purpose of literacy is communication.” (Quick-Guides to Inclusion, page 184)

Communication occurs all day, every day, in every aspect of our life and impacts our quality of life. Communication is fundamental in literacy development and for participation in learning.

Students who have complex communication needs are unable to communicate effectively using speech alone. They and their communication partners may benefit from using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods, either temporarily or permanently. Symbol-based communication is the “alternative” in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). To learn more about supporting students with complex communication needs, please see Access to Communication.

From an emergent literacy perspective, reading and writing develop concurrently and interrelatedly in young children, fostered by experiences that permit and promote meaningful interaction with oral and written language (Sulzby & Teale, 1991), such as following along in a big book as an adult reads aloud or telling a story through a drawing (Hiebert & Papierz, 1989). Through the concept of emergent literacy, researchers have expanded the purview of research from reading to literacy, based on theories and findings that reading, writing, and oral language develop concurrently and interrelatedly in literate environments (Sulzby & Teale, 1991).

In the past, the emphasis for students with significant disabilities was often on ‘life skills’ programming rather than communication supports and literacy instruction. Today we know that “there is no student too anything to be able to read and write” (Yoder, 2000). In fact, recent research shows that with high expectations, sound literacy instruction, and the support of assistive and communication technologies, individuals with cognitive disabilities can acquire literacy skills and demonstrate intelligence beyond what would have been predicted by test results. (Biklen & Cardinal, 1997; Broderick & Casa-Hendrickson, 2001; Erickson, Koppenhaver, & Yoder, 2002; Erickson, Koppenhaver, Yoder, & Nance, 1997; Koppenhaver et al, 2001; Ryndak, Morrison, & Sommerstein, 1999).

Starting with the Alberta Programs of Study

In Alberta, the starting point for instruction for all students is the provincial Programs of Study.

In Alberta, the starting point for instruction for all students is the provincial Programs of Study.

Alberta Education has designed sample optional templates for individualized program planning that focus on the use of instructional strategies to support the learning of all students. The templates incorporate all of the components currently required in the Standards for Special Education, Amended 2004, focusing on instructional planning and academic learning.

Template B is designed for students who have significant (i.e., moderate to severe) cognitive disabilities. The focus of this template is to create meaningful and successful learning opportunities using the program of studies as a starting point of instruction and to identify at least five individual learning goals (e.g., four Literacy and Communication goals and one goal related to Numeracy).

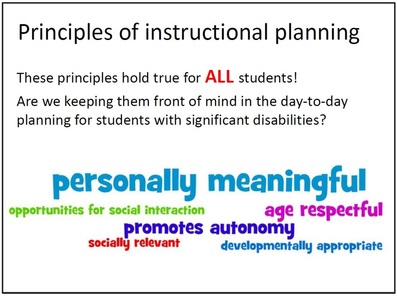

Individual learning goals should align with principle–based planning (i.e., personally meaningful, socially relevant, age respectful, developmentally appropriate, create opportunities to interact with peers, promote personal autonomy). Goals should increase students’ engagement in learning and academic success related to literacy and numeracy. (See Principles of Instructional Planning below.)

Template B can be found in the Inclusive Education Library as well as information and forms that can support this inclusive approach to instructional planning – http://www.learnalberta.ca/content/ieptLibrary/index.html.

Good literacy instruction is good for all students!

Many of the studies and literature surveys over the last four decades have a common finding – nothing replaces sound early literacy instruction, even when taking into consideration recent technical advances.

Research in emergent literacy shows that students with significant disabilities including those with complex communication needs, benefit from many of the same types of literacy activities used with typically developing children. However, students with disabilities may require more time and opportunity to benefit from this instruction. Regular participation in reading and writing activities is key to building understandings about print for ALL students.

The principles of planning for effective instruction are equally applicable to both students who are typical learners and students with significant disabilities. Designing meaningful and effective instruction for students with significant disabilities requires intentional planning that considers the strengths and needs of individual learners and takes into account best practices that work for all learners. For older emergent literacy learners, it is important to keep all activities age respectful.

To learn more about effective instructional practice for students with significant disabilities, including information, strategies and references, visit Learning for All.

Literacy for All: In conversation with Dr. Caroline Musselwhite

In this video, Dr. Caroline Musselwhite discusses why good literacy instruction is good for all students, including students with significant disabilities.

Learning Guide: Good Literacy Instruction is Good for All Students

Video length: 2 minutes 8 seconds

In this video, Dr. Caroline Musselwhite discusses the importance of meaningful repetition in learning, particularly for students with significant disabilities.

Learning Guide: Importance of Repetition and Variety in Learning

Video length: 1 minute 11 seconds

In this video, Dr. Caroline Musselwhite discusses what it means to be age-respectful when working with older students and how this can create richer opportunities for them to participate and learn.

Learning Guide: Engaging Older Students

Video length: 1 minute 12 seconds

Access to learning materials in the classroom

For students with motor impairments severe enough that they cannot hold or turn pages of books, hold or manipulate a pencil or type on a typical keyboard, they will require alternative access to learning materials in the classroom.

For students with motor impairments severe enough that they cannot hold or turn pages of books, hold or manipulate a pencil or type on a typical keyboard, they will require alternative access to learning materials in the classroom.

For some learners, physically holding a book and turning its pages may be difficult or impossible as might hearing and/or seeing books. Some learners may require page fluffers to allow them to turn pages, digital books on a device that allow the user to simply touch to turn the page, tactile or brailled books for the visually impaired, while others may require switch access to turn pages on digital books. To learn more about supporting access to books, please see Access to Books.

In order to develop literacy skills, all students need have a way to write using the full alphabet no matter what level of understanding they appear to have about print. For students with physical, cognitive or linguistic challenges, an alternative pencil can offer them a way to write and/or explore the alphabet while focusing the majority of their cognitive energy on text production. To learn more about alternative pencils, please see Access to Writing.

Determining where to start with literacy instruction

Answer the questions in the first box for the student you are working with. If you responded NO to any of these questions, you’ll implement the Daily Emergent Interventions. If you answered YES to all of the questions, you’ll implement the Daily Conventional Interventions as displayed below.

Daily Emergent Interventions:

Daily Conventional Interventions:

Important! Answering ‘yes’ to all of the above questions doesn’t necessarily mean that student is at a conventional literacy level but it does mean that they are ready to move to the conventional set of interventions.

If you have a class of students at both the Emergent and Conventional levels, use the combination of interventions as described below:

Combined emergent and conventional interventions:

- Shared Reading

- Alphabet & Phonological Awareness During Word Identification and Decoding

- Predictable Chart Writing

- Self-Selected Reading

- Structured and Independent Writing

- Guided Reading (Conventional Only)

- Writing Instruction (Conventional Only)